By Stuart Foxman

We hear a lot about allyship as one way to address systems of oppression. In fact, Dictionary.com called it “Word of the Year” in 2021. But for all its ubiquity, much confusion exists about what it means to be an effective ally. In this article, we explore how allyship can be best used to promote health equity.

In health care, as in any setting, certain groups can face all sorts of obstacles, which are obvious to those affected, but much less apparent to people whose privilege insulate them from the harsh realities encountered by others. Understanding the degree to which you might be privileged — and how that unearned privilege could be rigging the system — is the first step towards being a true ally.

“Allyship is an action and a skill,” says Dr. Saroo Sharda, CPSO Medical Advisor and Lead in Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. “It can’t be practised in isolation from deep and ongoing self-reflection on our own privilege and how we all — consciously or unconsciously — contribute to systems of inequality. We need to move the conversation away from solely interpersonal interactions to thinking about all the ways in which our health care system advantages some and disadvantages others.”

As the late sociologist Allan Johnson wrote: “What privilege does is load the odds one way or the other so that the chance of bad things happening to white people as a category of people is much lower than for everyone else, and the chance of good things happening is much higher. Privilege is not something a person can have, like a possession… Instead, it is a characteristic of the social system — like a rule in a game — in which everyone participates.”

Consequently, this may explain why so many people suggest that true allyship can only begin by helping disrupt the rules of the game.

Dr. Sharda says rather than seeing people in terms of “rescuer” or "victim,” or “good” or “bad,” we need to examine the structures and hierarchies that govern medical culture and work collectively to dismantle them because, ultimately, that will help us all.

Dr. Stephanie Nixon, the Vice-Dean of Health Sciences at Queen’s University, has written in-depth on the subject. She agrees with Dr. Sharda that we need to interrupt the systems that uphold injustices in the first place.

Speaking to one group of physicians, Dr. Nixon told them to think about it this way: “If allyship is a treatment, then we need to get the diagnosis right.”

Misdiagnose a health issue, she says, and the intervention won’t just be wrong, it could actually be harmful. The same is true in dealing with the multiple isms in our society, such as racism, ableism, and colonialism.

“Speak up when things need to be said, but don’t speak for people whose lived experiences you can’t possibly know”

Damage can persist if we focus only on the symptoms and ignore the disease, or if we examine issues in isolation. So allyship challenges us to look hard at privilege and prevailing systems of oppression. That can be uncomfortable, especially for those from dominant groups. It also has enormous consequences for health care.

It’s important to understand your own biases — the assumptions and stereotypes you might hold (e.g., about race, ethnicity, ability, gender, sexuality, etc.). The issue isn’t necessarily having biases, which is human — it’s failing to examine them.

“We do implicit bias tests, and someone said, ‘What if we don’t pass?’ The point isn’t to pass; it’s to unmask you to your biases so you can mitigate them,” says Dr. Roxanne Kirsch, a cardiac intensivist at SickKids in Toronto, and Associate Chief, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Wellness and Faculty Development for Perioperative Services.

Challenge the status quo

In a 2021 survey of Canadians by Maru/Blue, more than two-thirds of respondents said a culture of inclusion is more important than ever, and 77 percent said they believe they are actively promoting a more inclusive society. Yet, 58 percent were also unsure how to be an ally or define exactly what it entails.

Being an ally isn’t about good intentions, donating to a cause or sharing trendy social justice hashtags. It also isn’t a label you get to claim — it has to be earned.

“You can’t give yourself the title, and it’s not for your own benefit,” says Dr. Mojola Omole, a surgical oncologist in Toronto and a member of the board of the Black Physicians’ Association of Ontario.

She defines an ally as “a person who’s aware of their power and privilege and uses that to advantage others and challenge the status quo.”

Dictionary.com noted that when people look up “allyship,” the word that most often precedes it is “performative.” Performative allyship is playing the part, putting yourself at the centre and patting yourself on the back.

“I see more bad allyship than proper allyship,” says Dr. Jason Pennington, a staff surgeon at Scarborough Health Network, and Regional Indigenous Cancer Lead at the Central East Regional Cancer Program.

What’s a bad ally? Someone who thinks they’re a good ally, but who are all words and no action, says Dr. Pennington. That can happen at an organization level too, in spite of appearances.

“Too many institutions are happy with token positions, or EDI [equity, diversity and inclusion] that’s just isolated into this space and doesn’t permeate into the rest of the organization and the way it runs,” Dr. Pennington says.

Dr. Sarah Funnell, Associate Medical Officer of Health at Ottawa Public Health, says the worst allies are the ones who tell you what you need. Others are more benign, but don’t really do anything.

“Thinking nice thoughts doesn’t make you an ally,” says Dr. Funnell, who’s also Director of Indigenous Health in the Department of Family Medicine at Queen’s University.

More useful, she says, is the ally who speaks up against instances of oppression or the activist ally who shows “a longer-term commitment to a movement.”

“To be an ally, speak up when things need to be said, but don’t speak for people whose lived experiences you can’t possibly know,” says Dr. Kirsch.

In every way, allyship is a work in progress. It relies on meaningful relationships and takes time, says Dr. Franco Rizzuti, President of the Canadian Association of Physicians with Disabilities.

“It’s a longer process of committing yourself to understanding the issues from the perspective of people with lived experiences,” says Dr. Rizzuti, a public health and preventive medicine resident in Calgary. “You have to be consistent in behaviours and actions, emphasize social justice notions, and speak out against unjust policies.”

Understand biases and privilege

One way to capture what allyship stands for is to remember this acronym: A.L.L.Y. (credited to Kayla Reed, an American activist involved in the racial justice movement).

A – always centre the impacted.

L – listen and learn from those who live in oppression.

L – leverage your privilege.

Y – yield the floor.

Allyship literature further describes some of what A.L.L.Y. means.

Always centre the impacted by avoiding assumptions, understanding how others want to be supported, and defining if you’re helpful by whether someone else thinks you are. Don’t make this about you.

Listen and learn by finding out about those you want to support through their collective and individual stories. Don’t offload the burden of learning by making someone else educate you. Be curious and do your own homework.

“When I hear ‘we’re going to help you,’ I get my hackles up.”

Leverage your privilege by intervening when possible and shrinking power imbalances. You’re not there to save, but to share. If someone isn’t at the table, advocate to add them or reconfigure the table. Have a platform? Amplify the voices of those who don’t. If you have access to resources, ensure those who need them most also have access.

Yield the floor by talking less, listening more, stepping back and enabling others to fill the space.

The Black Physicians of Canada has a webpage devoted to allyship, which includes many examples of privilege. Adapted from that list, here are some questions to ask yourself. If you answer “no” to all, consider yourself privileged.

- Are you often mistaken for a non-physician? Do you have to make it very apparent that you are one?

- Do you feel pressure to perform without errors because of prejudices others have of you?

- Do you lack shared experiences with colleagues, or feel isolated or like an outsider in the social interactions that accompany your medical career?

- Do you have trouble advancing into leadership due to a lack of systemic support?

- Do you feel the need to stand up for yourself because you have few advocates?

- Do you have to ensure your strengths and accomplishments are recognized?

- Do you have to constantly remind yourself of your own self-worth?

While allyship requires action, it also calls for reflection. Recognize and find ways of acting on and interrupting your own biases or privileges, so you’re less likely to be influenced by them.

Be with, not above

In 2015, at the end of his residency, Dr. Michael Quon had a road cycling crash that caused a traumatic brain injury. He couldn’t work for a year and when he returned, with certain limitations, he saw different dimensions and shortcomings of allyship.

“To me, a big part of allyship is understanding and support. People who tried to understand my perspective and the challenges I was facing, that was allyship,” says Dr. Quon, an internal medicine specialist at The Ottawa Hospital and Queensway Carleton Hospital.

While that was helpful, Dr. Quon also noticed how some supposed allyship was rooted in making him adapt to a fixed system rather than making space for even minor scheduling modifications.

“It was how could I fit in to how we do things – that’s the older model,” says Dr. Quon, who serves on the board of the Canadian Association of Physicians with Disabilities. “There’s a notion that we have to change the people and bring them closer to the ‘norm’. The status quo was created by people of privilege for other people of privilege. Thinking outside of that is crucial.”

Self-proclaimed allies can go off the rails when they’re not walking with you and act like they’re above you, says Dr. Michael Anderson. That can happen with colleagues, health care initiatives or patient populations.

“When I hear ‘we’re going to help you,’ I get my hackles up. It’s problematic and comes from the wrong place,” says Dr. Anderson, who practises palliative care medicine and serves as the Strategic Lead, Indigenous Health for the University Health Network in Toronto.

He cites well-meaning researchers who fly into an Indigenous community, gather data, write a report about health care improvements, then wonder why nothing changes.

“It’s because they ask the wrong questions and it’s framed from an outsiders’ view,” Dr. Anderson says.

In contrast, he praises Toronto’s Indigenous cancer program, which is implemented in a way that reflects the unique needs of the population and honours the Indigenous path of well-being. The program reflects community voices because non-Indigenous health leaders came at it with humility, says Dr. Anderson. They knew what they didn’t know, wanted to learn and didn’t need to be seen as being in charge. “That resonated,” he says.

The coin model

On an individual level, attitudes, actions and advocacy add up. Still, it takes broader allyship efforts to erode the social structures that cause disadvantages and health inequities.

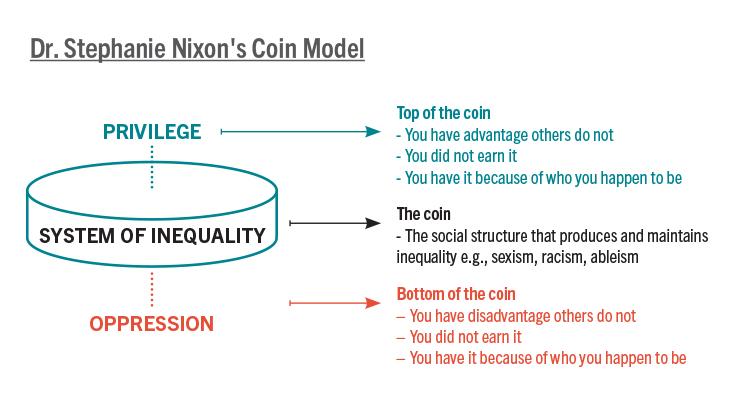

Dr. Nixon, who has presented on the topic of allyship to CPSO Council and its committees, described what she called the “coin model of privilege and critical allyship,” and the implications for health, in an article for the journal BMC Public Health. In it, she explained how the root causes of persistent health inequities are social, political and economic, as opposed to exclusively behavioural or genetic. Yet, even as we recognize that, a prevailing way of thinking puts obstacles in the way of progress.

“A barrier to transformative change is the tendency to frame these inequities as unfair consequences of social structures that result in disadvantage, without also considering how these same structures give unearned advantage, or privilege, to others,” she wrote.

How you think about the problem either widens or narrows possible solutions. To understand critical allyship, consider the coin analogy, where the two sides of a coin are groups of people.

The top of the coin represents the privileged groups, and the bottom, Dr. Nixon says, consists of the groups we tend to call marginalized, disadvantaged, vulnerable, high-risk, priority neighbourhoods, etc. These are the groups commonly targeted in health promotion research and interventions.

People at the bottom of the coin can be “pathologized,” says Dr. Nixon, i.e., there’s a problem there that needs fixing.

In her article, she wrote that viewing those atop the coin as “normal” or “average patients” is erroneous. “The top of the coin represents people who are the recipients of unearned and unfair benefits because their way of being is valued over others. The goal isn’t to move people from the bottom of the coin to the top, because both positions are unfair. Rather, the goal is to dismantle the systems causing these inequities.”

Consider support for people with disabilities. Is the issue achieving the norm of able-bodied people for those at the bottom of the coin (the “disabled”)? Then medical care and rehabilitation to “fix” the disability is the answer. Is the real issue the coin itself (the unfair social structure of ableism)? If so, Dr. Nixon says, “the cause of disability shifts.”

Using this model, she says health care professionals can practise critical allyship by reorienting their mindset. Don’t look at allyship as “saving” the less fortunate. Instead, critical allyship is about three commitments:

- Understand your role in upholding systems of oppression that create health inequities.

- Learn from the expertise of, and work in solidarity with, historically marginalized groups to help you understand and take action towards systems of inequality.

- Work to build insight among others in positions of privilege and mobilize in collective action under the leadership of people on the bottom of the coin.

“Framing allyship as a discrete act or identity outside of this wider perspective is a disservice and a distraction from the greater goal of creating a more just society where all are safe and well,” says Dr. Nixon.

The health of organizations and people

Strong demonstrations of allyship can promote the health of organizations and the well-being of their people. How might it also translate into better patient care?

When organizations are more respectful and equitable, everyone feels it, says Dr. Rizzuti. Staff and patients alike can see themselves there, he says, and “that builds an overall sense of inclusivity.”

Dr. Omole says people who’ve traditionally been in power can work to ensure there are diverse voices at the table, people who don’t look like them. Or, as she has seen, they can even give up their seat to allow others who have been marginalized to move up. The more that happens, she says, the better the chance for fresh thinking and approaches.

“You are able to have inputs of people’s different lived experiences to infuse into what you’re trying to do,” says Dr. Omole. “Diverse voices give you a better product — the product here being health care.”

Being an ally is defined partly by introspection, openness, educating yourself on the experiences of others, and understanding your part in perpetuating or breaking down barriers to progress. Those are valuable traits to have whether changing a system or interacting with patients one-on-one.

“We’ll get to a better place when we have different organizational cultures,” says Dr. Anderson.

In a culture where allyship thrives, people function differently. They feel heard, they’re comfortable being questioned and they have the ability to reflect. Does that rub off on professional behaviour and care? “Totally,” Dr. Rizzuti says.

“If you create a sense of cultural safety, and a space where the people serving you are humble and aware of their power and privilege, you’re creating a better work and clinical environment,” says Dr. Funnell.

Knowing your patients in the fullness of their lives is essential, and sometimes greater allyship at work can connect to that effort, says Dr. Omole. She says allyship can open your eyes to the experiences and mindsets of various groups, and that’s always helpful.

“It creates a better clinical environment because at the end of the day, our goal is to serve our patients,” Dr. Omole says. “If you don’t know your patients’ lived experiences, you’re not treating them well, you’re not treating them holistically.”

Equity for all

That type of allyship matters. So does the bigger picture of promoting health equity for all, and systemic and societal change. If that feels daunting, Dr. Nixon says to just remember that institutions are populated by people — us — who have agency. All of these systems were human-made and can be unmade, she says.

“To demonstrate authentic allyship,” says Dr. Funnell, “you have to have the courage to make change.”

“Systems of inequality play out at the interrelated levels of the institutional, interpersonal and internal. All levels matter and are tightly connected,” says Dr. Nixon.

When it comes to allyship, is being a doctor a benefit or an occupational hazard? On the one hand, empathy and listening are clinical skills that should transfer well to the allyship space. On the other hand, doctors are accustomed to being the experts, which can pose an I-know-what’s-best-for-you attitude.

“A lot of people who want to be an ally come with a paternalistic view: ‘I know how to fix you, I’m a doctor.’ But it’s really recognizing the issues from a more holistic view,” says Dr. Pennington.

One of the most important things an ally can do when people share their experiences and perspectives with you: just believe them.

It already happens every day in practice. If a patient says they’re in pain and describes how it affects their life or limits their abilities, you wouldn’t tell them they’re wrong or minimize their experiences. The same with allyship. In both cases, your job is to listen, says Dr. Rizzuti, not just to act as the healer.

Sometimes, resisting the urge to fix can be tough. “It puts the doctor in a place of vulnerability, where they don’t know everything,” Dr. Rizzuti says.

That’s a good thing. “Recognize that you are inherently a problem solver, but part of allyship is not providing a solution — but hearing,” says Dr. Kirsch.

On the path to equity, successes will look different, for colleagues, patients and the system as a whole. But it all starts with the same thing. “To demonstrate authentic allyship,” says Dr. Funnell, “you have to have the courage to make change.”

Learn More

- “The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for health”, BMC Public Health, Dec. 5, 2019,

- “Allyship and Inclusion at the Faculty of Medicine”, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto,

- “Indigenous Allyship Toolkit”, Montreal Urban Aboriginal Community Strategy Network,

- “Ally Toolkit”, Canadian College of Health Leaders

Dr. Stephanie Nixon’s Coin Model

The coin represents the social structure that produces and maintains inequality, such as racism, ableism, sexism.

At the bottom of the coin are the oppressed. They have disadvantages that others do not. They did not earn those disadvantages. At the top of the coin are people who have advantages that others do not. They did not earn those advantages. They have it because of who they happen to be.