Disabilities, bias and the “tragedy model”

By Stuart Foxman

When Anthony Frisina went to medical appointments as a child and teen, he noticed a phenomenon. The doctors would focus on his mother. They would address her, not him, asking her questions that he could have easily answered. This didn’t just happen when he was little, but when he has well into his teens.

“I felt like my comments were less valid, that I didn’t have autonomy,” Frisina recalls.

It wasn’t the only time Frisina, who was born with spina bifida, sensed that some in the health care system viewed him differently. At times, he felt patronized. Or pitied — “the tragedy model of disability,” as he puts it.

Other times, he has felt doctors see his condition first, with everything filtered through that lens. If he’s having pain or any number of other physical issues, then surely it must be related to his spina bifida.

On yet other occasions, Frisina suspects that a doctor has slotted him into a category, based on their academic knowledge of a disability rather than on his own lived experiences.

“We’re often grouped as opposed to being treated with the individuality we deserve,” says Frisina. “There are still stereotypes and stigmas around people with disabilities, where you’re deemed inferior.”

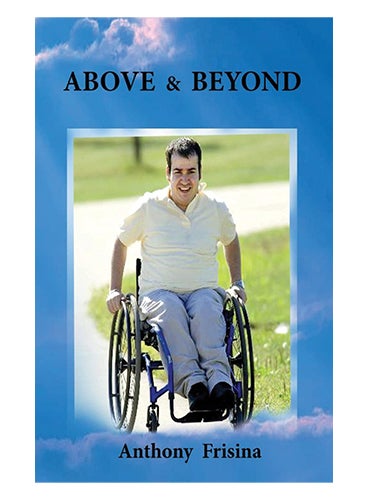

Today, Frisina is a media representative for the Ontario Disability Coalition. He created and produces a cable TV show in Hamilton, called Above and Beyond, about the importance of accessibility awareness and inclusion. When he sees a doctor, he wants the same thing as any other patient: personalized care, no preconceptions and support, Frisina says, to “live my best life”.

What can get in the way of that for patients with disabilities? If bias seeps into medical encounters, that may affect quality of care.

Unconscious feelings and assumptions

According to the Canadian Survey on Disability, more than 6.2 million Canadians aged 15 and over identify as having a disability. It’s assumed the actual numbers are even higher. The estimates of children living with a developmental or physical disability range from 200,000 to more than 800,000.

The term “disability” covers enormous ground and each type has its own range. Even referring to disabilities as a catch-all is a form of bias itself — as if all needs are common. Like anyone, people with disabilities have their own backgrounds, circumstances, challenges and hopes.

It’s folly to generalize about such an enormous and varied population. But that’s what bias and stereotyping do. They generalize, raising automatic feelings, judgments and presumptions about a person or group. Sometimes that’s happening at a subconscious level. What matters is how people act, based on what they think.

For anyone, health care providers included, it’s hard to change attitudes or actions if you don’t realize what’s behind them. One U.S. study, published in May 2020 in Rehabilitation Psychology, involved 25,000 health care workers. Most scored low on self-reported disability prejudice. Yet, almost 84 percent of these workers preferred non-disabled people on an implicit association test.

“Definitely there is an unconscious bias,” says Dr. Shawn Jennings.

He speaks not just as a doctor, but also a patient whose life transformed in an instant one spring day in 1999.

Back then, Dr. Jennings was a busy family physician in Saint John, NB. While driving, a car veered in front of him. He missed it by inches, but the force of slamming on his brakes caused whiplash. What he didn’t realize was that he had also torn the inner lining of a vertebral artery. A week later, when parking at a medical clinic, he felt like he had vertigo. Then, on May 13, 1999, he experienced a brainstem stroke. Dr. Jennings was 45.

For a time, that left Dr. Jennings with locked-in syndrome. He had full-body paralysis and could only blink — twice for yes, once for no. After six months, he regained some speech. Years of rehabilitation enabled him to use a wheelchair and gain partial function of his left arm.

While he had to retire from medicine, Dr. Jennings remained active. In 2002, he published a book, called Locked In Locked Out, which landed on the curriculum at the University of New Brunswick’s Faculty of Nursing. He served 10 years on the New Brunswick Premier’s Council on Disabilities and six years on the New Brunswick Health Council. Dr. Jennings is also a Past President of the Canadian Association of Physicians with Disabilities.

He says the stroke and its aftermath didn’t change his cognitive abilities or personality. But it did alter how people looked at him. To this day, in daily life and health care encounters, people will usually defer to his wife. He knows a condition like his is viewed as tragic. “But disability doesn’t mean bad or worse,” Dr. Jennings says.

His circumstances changed one day in 1999, but not his desire to be treated — by society and in health care — simply as a unique person, same as before.

Roots of ableism

Why might unconscious biases occur? Ableism, by definition, is a social prejudice against people with disabilities. It’s rooted in a value system where “standard” abilities are seen as superior.

"There are still stereotypes and stigmas around people with disabilities, where you’re deemed inferior."

This bias is built into the culture. Several studies have noted how ableism can present itself in health care as beliefs that:

- Disabilities are a deviation from the accepted norm;

- People with disabilities need (and want) to be “fixed”;

- A disability means worse health, a lower quality of life or suffering;

- People with disabilities are weak, dependent and vulnerable;

- Disabilities are a burden on the health care system;

- These patients take an inordinate amount of time and energy; and

- Medical interventions that benefit non-disabled people are inappropriate or futile for someone with a disability.

“Ableism equates a disability with diminished health, instead of a different way of being,” says Dr. Timothy Ross, PhD, a scientist at Bloorview Research Institute in Toronto and an expert on institutional ableism. “People can have a disability and feel healthy, fulfilled and happy.”

His research explores experiences of disability and ways to advance more accessible, inclusive and diverse communities. The prevailing attitudes in institutions are key.

“Practitioners should reflect on their conceptualizing,” says Dr. Ross. “If you think of a person as having a deficit, you may very well miss out on their intrinsic value, and on a better understanding of their needs and desires.”

In February 2021, the journal Health Affairs reported on a survey of more than 700 U.S. physicians, across seven specialities. Just over 82 percent said people with significant disabilities have a worse quality of life than non-disabled people. Only 41 percent were very confident about their ability to give the same quality of care to patients with a disability.

Lead author Dr. Lisa Iezzoni, a Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, says doctors “believe they have an understanding of disease that gives them a special ability to judge people’s lives.”

Ableism exists throughout society and there’s no reason to think the medical profession can avoid it, says Cindy Kabel-Mitchell. She’s VP of Family Alliance Ontario, a resource for people with disabilities, as well as their families and friends. Kabel-Mitchell has a daughter with a developmental disability. Her two other children are in health care, one as a paramedic, the other in medical school.

She says improvement starts by looking at disabilities not through a medical model lens, but through a social model lens. The latter suggests people are disabled by barriers in society, not by their difference in body or mind.

Doctors can provide exemplary care, but also aren’t immune from biases. They have consequences. How can biases play out when it comes to patient experiences and care? We explore that in the article entitled What Do Disability Biases Look Like in Practice?

You may be TAB

In teaching her university class, Heidi Janz shares a term that makes her students uneasy. “I refer to non-disabled people as TAB — temporarily able-bodied,” says Janz, who has cerebral palsy and is an adjunct professor with the University of Alberta’s John Dossetor Health Ethics Centre.

Anyone can come to live with a disability, from birth, any time, and also over time. Live long enough, and through illness, injury or the process of aging, you have a greater chance of having some sort of disability. The prevalence increases with age. One-third of Canadians aged 65-74 report having a disability, as do 47 percent of those 75 and older.

Janz says her students don’t like to think about the TAB concept. It’s no wonder. So much of any prejudice is about fear — the fear of the different or the “other.” In our society, says Janz, disabilities are seen as scary, associated with a loss of dignity and independence.

“In medicine, it’s unquestioned that a disability is bad,” she says.

That’s ableism. If you’re able-bodied now, you probably don’t want to contemplate the possibility (or inevitably) of having a disability. We can fear our potential future selves.